Can We Talk About Autistic Burnout as a Mental Health Risk? [Article]

![Can We Talk About Autistic Burnout as a Mental Health Risk? [Article]](https://static1.s123-cdn-static-a.com/uploads/5695988/2000_618937b71d552_filter_618937ce09137.jpg)

Rachel Worsley | 08/09/2020

There's a good chance that people eating yellow cupcakes at morning teas across Australia will be on the verge of autistic burnout, and no one is seeing the signs, writes Rachel Worsley.

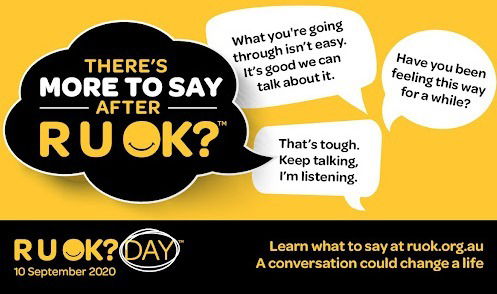

In Australia, we have a day known as R U OK Day. It is based on the deceptively simple concept of reaching out to someone and showing you care.

At the very least it builds connection. At best it reduces stigma and breaks the silence around mental illness and suicide. Many workplaces celebrate R U OK Day (10 September in 2020) by baking yellow and black R U OK cupcakes as part of a morning tea at which colleagues traditionally ask each other if they are OK.

I doubt many colleagues respond by explaining that they are experiencing autistic burnout. Yet, there’s a good chance people eating yellow cupcakes at morning teas across Australia (whether in-person or virtually) will be on the verge of autistic burnout. And no one is seeing the signs.

Who can blame them? The term autistic burnout has been talked about by autistic people for years, but has never received formal recognition by the medical profession.

It’s not the same as workplace burnout, either. In a 2020 study published in the journal Autism in Adulthood, US-based researchers argue that autistic burnout should be viewed as a distinct condition.

The researchers from the Academic Autism Spectrum Partnership in Research and Education research group interviewed 10 autistic people, analysed 19 public internet sources and used 9 interviews from a study on employment to come up with the following working definition of autistic burnout: “Autistic burnout is a syndrome conceptualised as resulting from chronic life stress and a mismatch of expectations and abilities without adequate supports. It is characterised by pervasive, long-term (typically 3+ months) exhaustion, loss of function, and reduced tolerance to stimulus.”

If you want the simile-friendly version to talk over a cupcake, you can quote the title of the research paper itself: “Having All of Your Internal Resources Exhausted Beyond Measure and Being Left With No Clean-Up Crew.”

The Main Features of Autistic Burnout

Let’s start with the three main features of autistic burnout according to that definition.

Chronic exhaustion: For many adults, chronic exhaustion comes from back-to-back deadlines or balancing childcare with the demands of paid employment. For autistic people, chronic exhaustion is the symptom of being left with no energy simply by the routine of daily life. As one autistic participant puts it: “The brutal truth is that for an autistic person, simply existing in the world is knackering -- never mind trying to hold down a job or having any sort of social life.”

Loss of function: The day-to-day skills that many people take for granted as an adult, such as getting out of bed and going to work (at least, in the pre-pandemic days) go out the window when you experience autistic burnout. For some participants in the study, depending on the severity of their burnout, those skills may never come back, or may be severely reduced. Even the act of talking can be too much, causing many to resort to non-verbal communication.

Reduced tolerance to stimulus: Autism often comes with being extra sensitive to stimuli such as noises. Autistic burnout makes it even more unbearable. Bright lights and noises create increased instances of meltdowns and shutdowns, driving autistic people to isolate themselves to relieve the burden on their senses. Often that might mean seeking comfort by hiding under the blankets.

Let’s return to the first part of the researchers’ definition, “chronic life stress and a mismatch of expectations and abilities without adequate supports”.

Life stress: The biggest life stress faced by most autistic people is through the act of masking, which means the suppression of traits like stimming (hand-flapping) or avoiding eye contact in an effort to fit in with the broader world.

Barriers to Support: Gaslighting, a term often mentioned in the context of domestic violence, is also used in the context of autistic people who are told that their troubles are their own fault or whose difficulties are dismissed as something that happens to everyone. Many autistic people also struggle to set boundaries, such as not understanding how to say “no” to requests or expectations, how to negotiate their own limits or how to self-advocate.

Expectations Outweigh Abilities: The tipping point for autistic burnout may arrive when the load on autistic people becomes more than they can manage with existing resources. They also may struggle to replenish resources or access support. To quote another simile raised by a participant: “Don’t expect us to keep operating at above-peak level. We’re like a light sedan car that’s driven like a semi-diesel hauler. We burn out when over-done.”

Imagine the collective impact of the above six factors on one autistic person. That’s something many autistic people will recognise.

How I cope with autistic burnout

My most recent autistic burnout left me hiding under a blanket for hours at a time. I kept the blinds shut and jammed headphones permanently over my ears. I turned to art to cope and wrote a ton of poetry, playing to my autistic strengths in creativity. I had external help with grocery orders and cooked meals delivered direct to my house. While I toned down my social activity, I kept in touch through text messaging, since I didn’t have the energy or inclination to talk.

I am the founder and CEO of a global media company. Autistic burnout is part of my reality and I have developed my own recovery techniques. But unfortunately workplaces and mental health professionals are not yet adequately informed.

How Workplaces and Mental Health Services can Help

The researchers found the following strategies helped autistic people recover from autistic burnout. In no particular order, they include:

- Acceptance and social support, such as individual, community and peer support.

- Allowing autistic people to be themselves, such as hiding under a blanket, unmasking (like choosing not to make eye contact with people) and playing to autistic strengths.

- Being encouraged to ask for formal accommodations, such as wearing headphones in the workplace or receiving help with cleaning the house.

- Reducing overall load, such as taking time off work, withdrawing from social activities and reducing the number of activities.

- Encouraging self-advocacy, such as setting boundaries, asking for help and building healthy habits.

- Building self-knowledge, such as recognising early signs of burnout and understanding patterns and making strategic decisions.

Interestingly, mental health assistance does not rate highly on that list of solutions for managing autistic burnout. I can hear the objections already. “Withdrawing from social activities” is a sign of depression, surely, if you go by the traditional mental health awareness messaging.

That’s true, but what if people asked the person feeling this way the simple question: “why”? The follow up question to “R U OK”? Why are you feeling withdrawn from such activities? If the answer is along the lines of: “Because my senses are overwhelmed and socialising exhausts me more than usual and I’m not coping”, then withdrawal is a healthy strategy to suggest for a person struggling with autistic burnout. If the answer is more like, “I’m sad and don’t enjoy life anymore”, then that sounds more like depression.

That’s why we need this research. That’s why we need to get better at publicising this important piece of public health messaging. Workplaces and mental health services will be better equipped to figure out which burnout recovery strategies do more good than harm for autistic people.

So this R U OK Day, you might feel OK to share your personal knowledge over cupcakes at work. And if that’s too difficult, share a link to this article.